TL;DR

- Generative AI is experiencing an unprecedented growth trajectory, and is anticipated to expand from $40 billion in today’s marketplace to a staggering $1.3 trillion by 2032.

- The rise of generative AI has sparked complex ethical and legal debates, including issues surrounding copyright, intellectual property rights, and data privacy.

- With its potential to disrupt traditional creative work, AI’s role in the creative industries has become a critical point during the Hollywood strikes.

- Scholars argue that while generative AI can mimic certain aspects of human creativity, it lacks the ability to produce genuinely novel and unique works.

- In the future, generative AI could be embraced as an assistant to augment human creativity, be used to monopolize and commodify human creativity, or place a premium on “human-made” — or all three.

READ MORE: Why AI will ultimately lose the war of creativity with humanity (BBC)

In the age of artificial intelligence, the concept of creativity has become a fascinating battleground. The Hollywood strikes have thrown the debate into sharp relief, pitting guild members against major studios seeking to disrupt a successful century-old business model by adopting Silicon Valley’s “move fast and break things” ethos.

Madeline Ashby at Wired deftly outlines the stakes for the striking writers and actors. “Cultural production’s current landscape, the one the Hollywood unions are bargaining for a piece of, was transformed forever 10 years ago when Netflix released House of Cards. Now, in 2023, those same unions are bracing for the potential impacts of generative AI,” she writes.

“As negotiations between Hollywood studios and SAG heated up in July, the use of AI in filmmaking became one of the most divisive issues. One SAG member told Deadline ‘actors see Black Mirror’s “Joan Is Awful” as a documentary of the future, with their likenesses sold off and used any way producers and studios want.’

“The Writers Guild of America is striking in hopes of receiving residuals based on views from Netflix and other streamers — just like they’d get if their broadcast or cable show lived on in syndication. In the meantime, they worry studios will replace them with the same chatbots that fanfic writers have caught reading up on their sex tropes.”

READ MORE: Hollywood’s Future Belongs to People—Not Machines (Wired)

AI researcher Ahmed Elgammal, a professor at the Department of Computer Science at Rutgers University, where he leads the Art and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory, recently sat down with host Alex Hughes on the BBC Science Focus Instant Genuis podcast to discuss the limits of AI against human creativity.

In the episode “AI’s fight to understand creativity,” which you can listen to in the audio player below, Elgammal explores the capabilities and limitations of AI in generating images, the ethical dilemmas surrounding copyright, and the profound distinction between AI-generated images and human-created art. This conversation sheds light on the complex relationship between machine learning and the uniquely human quality of creativity, setting the stage for the ongoing debate at the intersection of art and technology.

“The current generation of AI is limited to copying the work of humans. It must be controlled largely by people to create something useful. It’s a great tool but not something that can be creative itself,” the AI art pioneer tells Hughes.

“We must be conscious about what’s happening in the world and have an opinion to create real art. The AIs simply don’t have this.”

The Growth and Impact of Generative AI

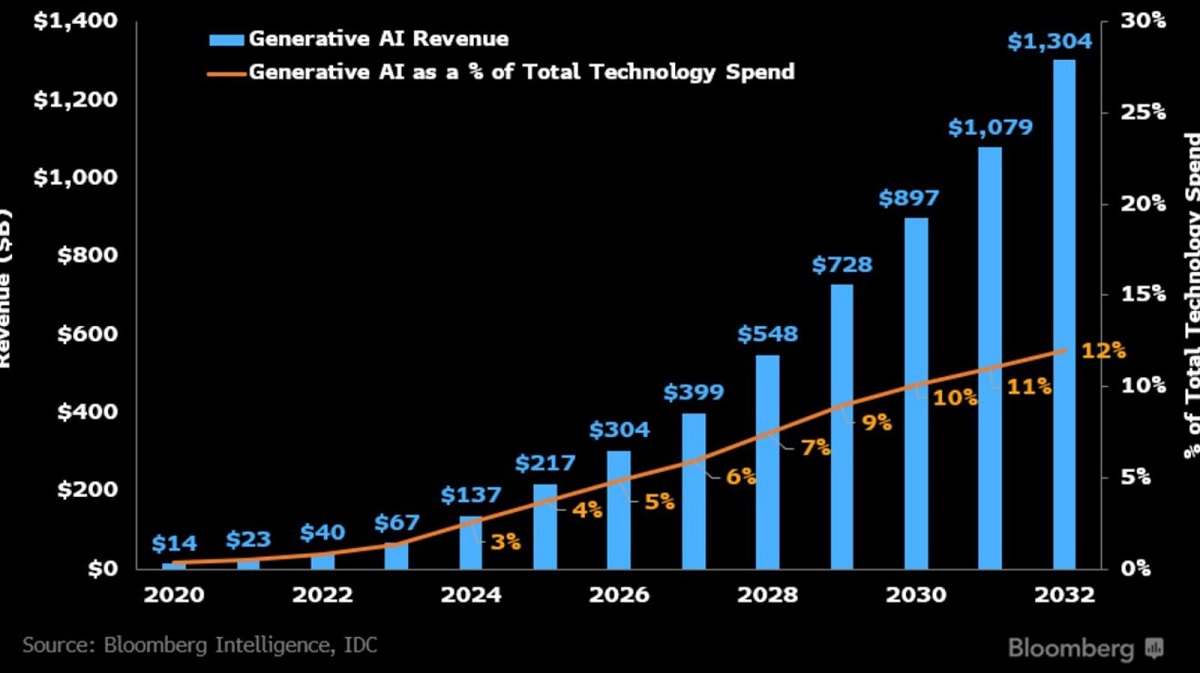

Generative AI is experiencing an unprecedented growth trajectory, with Bloomberg Intelligence forecasting its expansion from $40 billion in today’s marketplace to a staggering $1.3 trillion by 2032.

Bloomberg’s latest report, “2023 Generative AI Growth,” demonstrates that this growth is not confined to mere numbers, but represents a fundamental shift in the way industries operate.

“The world is poised to see an explosion of growth in the generative AI sector over the next 10 years that promises to fundamentally change the way the technology sector operates,” Mandeep Singh, senior technology analyst at Bloomberg Intelligence and lead author of the report, emphasizes. “The technology is set to become an increasingly essential part of IT spending, ad spending, and cybersecurity as it develops.”

READ MORE: Generative AI to Become a $1.3 Trillion Market by 2032, Research Finds (Bloomberg Intelligence)

Reflecting a broader trend in the technological landscape, Bloomberg predicts that generative AI will move revenue distribution away from infrastructure and towards software and services.

Voicebot.ai editor and publisher Bret Kinsella analyzes this shift on his Synthedia blog. “The report shows that 85% of the revenue in 2022 was related to computing infrastructure used to train and operate generative AI models,” he writes. “Another 10% is dedicated to running the models, also known as inference. Generative AI software and ‘Other’ services (mostly web services) accounted for just 5% of the total market.”

But that revenue distribution will change radically over the next decade, he notes. “In 2027, researchers estimate infrastructure-related revenue to decline from 95% of the market to just 56%. The figure will be about 49% in 2032.”

As a result, says Kinsella, “generative AI training infrastructure will become a $473 billion market while generative AI software [will] reach $280 billion, and the supporting services will surpass $380 billion. This may seem outlandish to forecast a software segment of a few hundred million dollars will transform into a few hundred billion in a decade. However, the impact of generative AI is so far-reaching it makes everyone rethink old assumptions.”

Specialized generative AI assistants and code generation software are emerging as powerful tools, allowing businesses to leverage AI in innovative ways. However, this growth also brings challenges. Kinsella highlights the need for caution, pointing out that the rapid adoption of AI technologies raises questions about accessibility, ethics, and regulation. Balancing innovation with responsible development will be a key consideration as generative AI continues to evolve, requiring new regulations and ethical considerations in areas such as copyright, data privacy, and algorithmic bias.

READ MORE: Generative AI to Reach $1.3 Trillion in Annual Revenue — Let’s Break That Down (Synthedia)

Human Creativity Trumps AI

Creativity is a complex and multifaceted subject, inspiring fierce debate since long before the days of Dada artists such as Marcel Duchamp, who in 1917 displayed a sculpture comprising a porcelain urinal signed “R. Mutt.” Much like pornography, people find art — and creativity, the driving force behind all art — difficult to define. “I don’t know much about art, but I know what I like,” the popular saying goes.

Elgammal draws a clear line between AI-generated images and human-created art. “AI doesn’t generate art, AI generates images. Making an image doesn’t make you an artist; it’s the artist behind the scene that makes it art,” he tells Hughes. In other words, human creativity will always trump AI.

AI’s ability to generate realistic images is both impressive and concerning. While the technology has advanced significantly, now capable of delivering lifelike, photorealistic “AI clones,” it is not without flaws. Errors in AI-generated images, such as distorted fingers and hands, and the inability to produce something truly new are both significant limitations.

An article by Chloe Preece and Hafize Çelik in The Conversation explores AI’s inability to replicate human creativity, arguing that while AI can mimic certain aspects of creativity, it falls short in producing something genuinely novel and unique.

The key characteristic of what they call AI’s creative processes “is that the current computational creativity is systematic, not impulsive, as its human counterpart can often be. It is programmed to process information in a certain way to achieve particular results predictably, albeit in often unexpected ways.”

The duo cites Margaret Boden, a research professor of cognitive science at the University of Sussex in the UK, on the three types of creativity: combinational, exploratory, and transformational.

“Combinational creativity combines familiar ideas together. Exploratory creativity generates new ideas by exploring ‘structured conceptual spaces,’ that is, tweaking an accepted style of thinking by exploring its contents, boundaries and potential. Both of these types of creativity are not a million miles from generative AI’s algorithmic production of art; creating novel works in the same style as millions of others in the training data, a ‘synthetic creativity,’” they write.

“Transformational creativity, however, means generating ideas beyond existing structures and styles to create something entirely original; this is at the heart of current debates around AI in terms of fair use and copyright — very much uncharted legal waters, so we will have to wait and see what the courts decide.”

But the main flaw Preece and Çelik find with generative AI is its consumer-centric approach. “In fact, this is perhaps the most significant difference between artists and AI: while artists are self- and product-driven, AI is very much consumer-centric and market-driven — we only get the art we ask for, which is not perhaps, what we need.”

READ MORE: AI can replicate human creativity in two key ways – but falls apart when asked to produce something truly new (The Conversation)

The Three Body Problem: Copyright, Intellectual Property and Ethics

The rapid evolution and widespread adoption of generative AI has also given rise to a complex web of ethical and legal challenges. As AI systems become more sophisticated in generating content that closely resembles human creativity, questions surrounding copyright, intellectual property rights, data privacy, and algorithmic bias have come to the forefront.

“This is far more than a philosophical debate about human versus machine intelligence,” technology writer Steve Lohr notes in The New York Times. “The role, and legal status, of AI in invention also have implications for the future path of innovation and global competitiveness.”

The Artificial Inventor Project, a group of intellectual property lawyers founded by Dr. Ryan Abbott, a professor at the University of Surrey School of Law in England, is pressing patent agencies, courts and policymakers to address these questions, Lohr reports. The project has filed pro bono test cases in the United States and more than a dozen other countries seeking legal protection for AI-generated inventions.

“This is about getting the incentives right for a new technological era,” Dr. Abbott, who is also a physician and teaches at the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA, told Lohr.

READ MORE: Can A.I. Invent? (The New York Times)

Elgammal spends a considerable amount of time delving into these complex issues. He identifies a three-way copyright problem that has emerged with the current generation of AI image tools. The stakeholders include the innovator, who might inadvertently violate the copyright of other artists; the original artist, whose work might be transformed or mixed without consent; and the AI developer, the company that develops and trains the AI system based on these images.

This is a new and significant problem, and one that current copyright laws are not equipped to handle. The situation is further complicated by the fact that the latest models are trained on billions of images, often without proper consent, leading to a messy situation where copyright infringement is difficult to track and enforce.

“The copyright problem comes with the current generation of imagery tools that are mainly trained on billions of images,” he says. “However, this wasn’t an issue a couple of years ago, when artists used to have to use AI through certain models that were trained using the artist’s own images.”

While training models on billions of images taken from the internet might not directly violate copyright law (since the generated images are transformative rather than derivative), it is still considered unethical, Elgammal insists.

AI’s role in misinformation is another major consideration, he says. “How can we control the data given to an AI?” he asks. “There are different opinions on everything from politics to religion, lifestyle and everything in between. We can’t censor the data it’s given to support certain voices.”

Elgammal also raises concerns about the environmental impact of AI, noting that just “training the API these models use takes a lot of energy.”

Running on Graphics Processing Units (GPUs), known for their high energy consumption, this training can last for days or weeks, iterating over billions of images. This phase forms the bulk of the energy footprint, reflecting a significant demand on power resources. The generation of images, even after training, continues to require substantial energy. Running the models on GPUs to create images adds to the energy consumption, making the entire process from training to generation a power-hungry endeavor.

Lost in Translation

As generative AI tools become increasingly more sophisticated, the potential for collaboration between humans and artificial intelligence increases exponentially. Elgammal explains how platforms designed for artists to train AI on their own data can lead to new forms of artistic expression, where the machine becomes an extension of the artist’s creativity.

But the newest text-to-image tools, trained on billions of publicly available images, actually decreases the level of creativity possible with generative AI, he argues. “With text prompting, as a way to generate, I think we are losing the fact that AI has been giving us ideas out of the box, or out of [the] ordinary, because now AI is constrained by our language.”

One of the most interesting things about generative AI, says Elgammal, is its ability to visually render our world in novel ways. But text-to-image tools compel AI to look at the world “from the lens of our own language,” he explains. “So we added a constraint that limit[s] the AI’s ability to be imaginative or be engineering interesting concepts visually.”

Language is still useful in other contexts, however, “because if you are using AI to generate something, linguistic text or something very structured like music, that’s very important to have language in the process,” he says. “So we have a long way to go in terms of how AI can fit the creative process for different artists. And what we see now is just still early stages of what is possible.”

AI as Creative Assistant

Artificial intelligence, it turns out, might be best employed as a creative assistant.

Elgammal likens generative AI to a “digital slave” that can be used to help artists increase their creative output. “Fortunately, the AI is not conscious. So having a digital slave in that sense is totally fine,” he says. “There’s nothing unethical about it.”

He compares the relationship between artist and AI to a director and film crew, or Andy Warhol’s Factory, which had dozens of assistants in varying capacities that allowed Warhol to carry out his creative vision. “But an emerging artist doesn’t have this ability. So you can use AI to really help you create things at scale.”

An article in the Harvard Business Review by David De Cremer, Nicola Morini Bianzino, and Ben Falk explores this idea further in one of three different — but not necessarily mutually exclusive — possible futures they foresee with the use of generative AI.

In this scenario, AI augments human creativity, facilitating faster innovation and enabling rapid iteration, but the human element remains essential.

“Today, most businesses recognize the importance of adopting AI to promote the efficiency and performance of its human workforce,” they write, citing applications such as health care, inventory and logistics, and customer service.

“With the arrival of generative AI, we’re seeing experiments with augmentation in more creative work,” they continue. “Not quite two years ago, Github introduced Github Copilot, an AI ‘pair programmer’ that aids the human writing code. More recently, designers, filmmakers, and advertising execs have started using image generators such as DALL-E 2. These tools don’t require users to be very tech savvy. In fact, most of these applications are so easy to use that even children with elementary-level verbal skills can use them to create content right now. Pretty much everyone can make use of them.”

The value proposition this represents is enormous. “The ability to quickly retrieve, contextualize, and easily interpret knowledge may be the most powerful business application of large-language models,” the authors note. “A natural language interface combined with a powerful AI algorithm will help humans in coming up more quickly with a larger number of ideas and solutions that they subsequently can experiment with to eventually reveal more and better creative output.”

The Future of Generative AI

De Cremer, Bianzino and Falk outline two other possible scenarios for the future of generative AI: one where machines monopolize creativity, and another where “human-made” commands a premium. Again, these aren’t mutually exclusive; any or all of them could occur — and be occurring — at the same time.

What the writers call a nascent version of this first scenario could already be in play, they caution. “For example, recent lawsuits against prominent generative AI platforms allege copyright infringement on a massive scale.”

Making the issue even more fraught is the gap between technological progress and current intellectual property laws. “It’s quite possible that governments will spend decades fighting over how to balance incentives for technical innovation while retaining incentives for authentic human creation — a route that would be a terrific loss for human creativity.

“In this scenario, generative AI significantly changes the incentive structure for creators, and raises risks for businesses and society. If cheaply made generative AI undercuts authentic human content, there’s a real risk that innovation will slow down over time as humans make less and less new art and content.”

The resulting backlash could put even more of a premium on “human-made,” they argue. “One plausible effect of being inundated with synthetic creative outputs is that people will begin to value authentic creativity more again and may be willing to pay a premium for it.”

READ MORE: How Generative AI Could Disrupt Creative Work (Harvard Business Review)

Businesses that find success using generative AI tools “will be the ones that also harness human-centric capabilities such as creativity, curiosity, and compassion,” according to MIT Sloan senior lecturer Paul McDonagh-Smith.

The essential challenge, he said during a recent webinar hosted by MIT Sloan Executive Education, lies in determining how humans and machines can collaborate most effectively, so that machines’ capabilities enhance and multiply human abilities, rather than diminish or divide them.

It’s up to humans to add the “creativity quotient” to use technologies like generative AI to their full potential. For organizations, this means creating processes, practices, and policies that empower people to be creative to maximize the power of transformative technologies.

“Boosting your creativity quotient will optimize the use of large language models and generative AI,” he said. “It will also put all of us in a much better place in terms of how we interface with AI and technology in general.”

READ MORE: Why generative AI needs a creative human touch (MIT Sloan)

Founders Fund principal Jon Luttig sees three distinct patterns of behavior in regards to the rapid rise of generative AI: hope, cope, and mope.

“With a sudden phase change driven by very few people, many technologists fear that the new world we’re entering will leave them behind,” he writes on Substack. “This fear creates hallucinations including hope (the LLM market deployment phase will unfold in a way that benefits me), cope (my market position isn’t so bad), and mope (the game is already over, and I lost).”

These hallucinations, as the venture capitalist dubs them, “propel hyperbolic narratives around foundation model FUD [Fear, Uncertainty and Doubt], open source outperformance, incumbent invincibility, investor infatuation, and doomer declarations. It’s hard to know what to believe and who to trust.”

Luttig seeks to dispel these myths, contending that there’s still plenty of room for AI startups to flourish alongside players like Microsoft and Google. The people who want to slow AI down, he argues, are just the copers and mopers who fear that they’re on the wrong end of the equation.

Tell that to the writers and actors out on the picket lines.

READ MORE: Hallucinations in AI (John Luttig)